Typhu88 – Sân chơi cá cược đẳng cấp toàn cầu

Typhu88 còn được biết với tên TP88 – là nhà cái cá cược online uy tín, có tầm ảnh hưởng lớn trên thị trường giải trí Việt. Sân chơi này thành lập từ năm 2015 và đã được cấp phép bởi Malta Gaming Authority (MGA) và Ủy ban cờ bạc Vương quốc Anh (UKGC). Nhà cái TP88 cung cấp sân cá cược cho bet thủ với các tựa game cuốn hút, kịch tính cùng tiền thắng cược siêu hấp dẫn.

ĐỐI TÁC UY TÍN CỦA TYPHU88

Khái quát chung về nhà cái Typhu88

Nền tảng nhà cái Typhu88 – TP88 đã nhanh chóng khẳng định tên tuổi của mình trong ngành cá cược với sự đa dạng về dịch vụ cá cược cùng và trải nghiệm người dùng vượt trội.

Mỗi sản phẩm mà Typhu88 mang đến hội viên đều có đặc điểm thú vị riêng. Game thủ được trải nghiệm không gian cược cuốn hút, hấp dẫn và an toàn.

Lý do Typhu88 được nhiều người chơi yêu thích

Trong thị trường cược trực tuyến sôi động như hiện nay, để trở thành một thương hiệu nổi tiếng được nhiều người biết đến là điều không hề dễ dàng. Nếu muốn duy trì cũng như phát triển vững vàng, sân chơi cần có những điểm ấn tượng riêng. Dưới đây là một số ưu điểm nổi bật của Typhu88 so với những địa chỉ cá cược khác:

Giao diện Typhu88 dễ nhìn

Giao diện cổng game là yếu tố gây ấn tượng ban đầu cho người chơi. Website Typhu88 được thiết kế dễ sử dụng, bắt mắt. Các nút bấm, biểu tượng, menu đều bố trí rất khoa học. Điều này giúp tăng sự hứng thú cũng như tạo điều kiện thuận lợi giúp người chơi săn thưởng mượt mà.

Chất lượng dịch vụ tại Typhu88 chuyên nghiệp

Đội ngũ support của nhà cái Typhu88 được đào tạo bài bản, có kiến thức sâu rộng đối với vấn đề cá cược trực tuyến. Mọi khó khăn hay thắc mắc của anh em đều được tiếp nhận và xử lý nhanh chóng. Cổng game cũng cung cấp nhiều phương thức hỗ trợ như: gọi hotline, chat live, liên hệ Email, Telegram. Người chơi sẽ không bị mất phí khi kết nối đến nhân viên hỗ trợ của nhà cái.

Typhu88 bảo mật tài khoản hội viên tuyệt đối

Tính năng bảo mật được cổng game quan tâm đầu tư với sự tiên tiến cao. Nhờ vậy mà dữ liệu người chơi hạn chế tình trạng bị hacker xâm nhập. Ngoài ra, mọi giao dịch nạp và rút tiền đều bảo vệ an toàn qua nhiều lớp mã hóa.

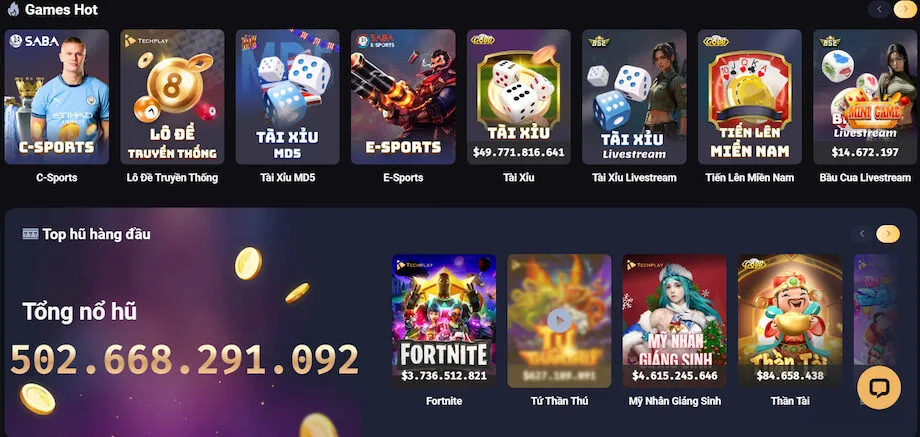

Kho game Typhu88 đẳng cấp quốc tế

Kho game chất lượng là một trong các yếu tố giúp Typhu88 nhận về đánh giá tích cực của cộng đồng cược thủ. Trên trang chủ hiển thị rõ ràng những sản phẩm giải trí đình đám. Bet thủ có thể thoải mái chọn game bài, nổ hũ, xổ số, thể thao, live casino… để săn thưởng. Những trò chơi này đều do đơn vị uy tín phát hành nên chất lượng giải trí trực tuyến luôn đạt chuẩn. Chỉ với một cú click chuột, người chơi sẽ được đắm chìm vào không gian săn thưởng hấp dẫn.

Trả thưởng Typhu88 hấp dẫn

Typhu88 không ngại chi khoản tiền lớn vào việc trả thưởng cho hội viên may mắn chiến thắng. Nhờ vậy mà game thủ có thêm cơ hội săn về túi mỗi ngày những khoản tiền khủng. Mọi thao tác giao dịch nhà cái Typhu88 hỗ trợ đều đơn giản hóa thao tác đảm bảo sự tiện lợi cho người chơi. Anh em có thể nạp và rút tiền bằng nhiều phương thức khác nhau như: Code Pay, ví điện tử, tiền ảo, hoặc thẻ cào. Bên cạnh đó, sân cược đã thiết lập mối liên kết chặt chẽ với các ngân hàng uy tín tại Việt Nam nhằm mang đến trải nghiệm giao dịch tiện lợi cho tất cả người chơi.

Khám phá kho cược hấp dẫn có tại Typhu88

Nhà cái Typhu88 mang đến hội viên kho trò chơi với rất nhiều sản phẩm cược hot và được cập nhật liên tục. Sau đây là thông tin về những sản phẩm giải trí online đang có tại sân chơi này cho anh em tham khảo:

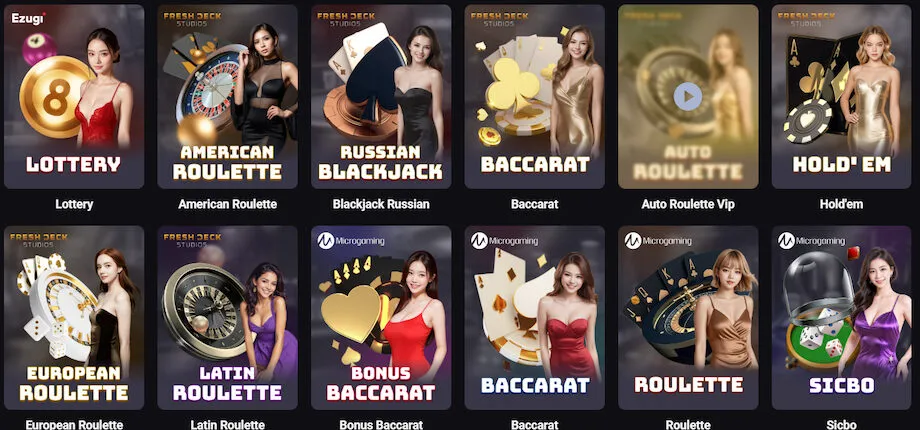

Live Casino Typhu88

Khi tham gia Live Casino Typhu88 anh em sẽ tìm thấy phút giây trải nghiệm chân thực, thú vị và đầy kích thích như đang đặt cược trực tiếp ở những sòng bạc quốc tế. Mỗi bàn chơi đều có sự hỗ trợ của Dear nóng bỏng chia bài. Nhờ có sự tham gia điều phối của họ mà trận đấu trở nên hưng phấn, cuốn hút hơn.

Bên cạnh đó, sảnh cược cũng thiết kế nhiều phòng tạo sự chọn lựa thoải mái và phù hợp với điều kiện tài chính của từng cược thủ. Sảnh live casino Typhu88 nổi bật với các sản phẩm như: Sicbo MD5, Tài Xỉu, Xóc Đĩa, Roulette, Blackjack, … Tất cả trò chơi đảm bảo sự minh bạch, công bằng cùng chất lượng vượt trội.

Thể thao Typhu88

Nhà cái Typhu88 cho phép người chơi tham gia cá cược đa dạng với các bộ môn thể thao như: bóng đá, cầu lông, quần vợt, bóng chuyền,… Sân chơi còn cung cấp tỷ lệ kèo cạnh tranh được nghiên cứu bởi đội ngũ chuyên gia hàng đầu.

Thành viên có thể tham gia dự đoán trận đấu, cá cược trực tiếp hoặc theo dõi cược khi trận đấu đang diễn ra. Tỷ lệ kèo được nhà cái công bố minh bạch và cạnh tranh nhất. Anh em cược thủ ngại gì mà không thử sức cá độ thể thao của cổng game ngay.

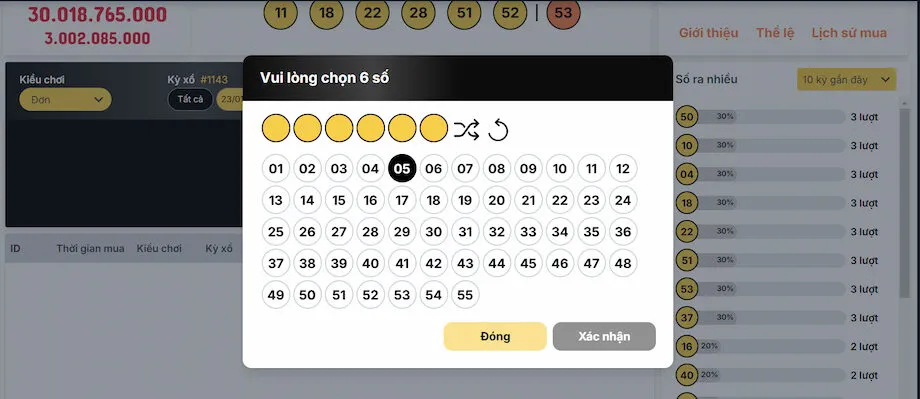

Xổ số Typhu88

Xổ số Typhu88 đem đến cho người chơi những trải nghiệm giải trí tuyệt vời với hàng loạt tựa game đình đám như Xổ số 3 miền, Keno, Max4D. Tỷ lệ thưởng cực hời giúp hội viên thu về số tiền thưởng lớn nếu may mắn dự đoán trúng. Đặc biệt, cổng game còn chia sẻ nhiều thông tin soi cầu thú vị hỗ trợ hội viên sớm tìm ra con số tài lộc để chốt cược.

Table Game Typhu88

Sảnh cược hot hit có tại Typhu88 đã gọi tên Table Game là sự lựa chọn lý tưởng của những ai yêu thích sự kịch tính và thử thách. Với những trò chơi siêu hấp dẫn như: Cao thấp, Tài xỉu, Xóc đĩa, Bầu cua, Sicbo tài phú, Three card poker, Sicbo, Xèng tài xỉu, Dragon & Tiger,… anh em được trải nghiệm những màn cược giải trí đầy thú vị và hội rinh về những phần thưởng siêu lợi nhuận.

Game bài Typhu88

Khi đến với sảnh chơi bài tại Typhu88 đảm bảo các anh em sẽ mê mẩn với những tựa game bài tại đây mà không thể nào rời mắt được. Tại đây bạn có thể khám phá các trò chơi như Tiến lên miền Nam, Phỏm, Mậu Binh và rất nhiều trò chơi bài phổ biến khác.

Nổ hũ Typhu88

Typhu88 với cung cấp vô số chủ đề quay hũ đặc sắc. Mỗi tựa game đưa người chơi bước vào thế giới kỳ diệu đầy màu sắc và trải nghiệm mới mẻ.

Bắn cá Typhu88

Bắn cá Typhu88 xuất hiện khá lâu nhưng độ hot theo thời gian không hề thuyên giảm. Nhà cái Typhu88 kết hợp cùng một vài đơn vị cung cấp game có tiếng cho ra mắt những sản phẩm có hình ảnh chất lượng và chỉn chu. Anh em được đắm chìm vào thế giới đại dương với đa dạng sinh vật biển.

Người chơi có thể tham gia quay hũ đặc sắc với những trò chơi hấp dẫn như: Vua săn cá, Đại chiến Godzilla, Biệt đội trên không, Bắn cá thiên đường, Bắn cá may mắn, Bắn cá Oneshot, Jackpot Fishing, Happy Fishing, Bắn cá Thủy Hử, Tỷ phú đại dương, Bắn cá phát tài, Dragon Fortune, Royal Fishing,…

Quay số Typhu88

Quay số tại Typhu88 luôn là lĩnh vực được nhiều người chơi yêu thích bởi cách thức chơi đơn giản và tỷ lệ thắng vượt trội. Mỗi ván chơi không chỉ là cơ hội để người chơi trải nghiệm mà còn được học hỏi và nâng cao kỹ năng chơi game của mình. Nếu yêu thích toán học thì Quay số Typhu88 chính là sự lựa chọn tuyệt vời dành cho bạn.

Game nhanh Typhu88

Game nhanh Typhu88 là một trò chơi trực tuyến được thiết kế để cung cấp trải nghiệm giải trí và kiếm tiền nhanh chóng. Mỗi ván game chỉ kéo dài vài phút mỗi lượt chơi phù hợp với những dân chơi đang tìm kiếm niềm vui tức thì mà không mất nhiều thời gian.

Một số sản phẩm game nhanh nổi bật tại Typhu88 mà anh em có thể khám phá như: Siêu dò mìn, Đường bay tỷ phú, Thả bóng ăn tiền, So bài cao thấp, Lắc xúc xắc, Đường banh cân não, Trên dưới, Keno Vietlott, Keno lộc phát, Quay số dân gian, Xếp kim cương, Hoa quả đại chiến, Numbers game,…

Đá gà Typhu88

Đá gà Typhu88 được đánh giá là một môi trường cá cược đầy lôi cuốn. Tại đây, game thủ được tận hưởng những trận đá gà đẳng cấp nhất và tham gia cá cược hợp pháp. Cổng game đã thiết lập mạng lưới hợp tác rộng rãi với nhiều trường đá gà có tên tuổi. Game thủ được mãn nhãn trước những màn so tài gay cấn giữa các chiến kê chuyên nghiệp.

Hiện Typhu88 cung cấp nhiều hình thức chọi gà khác nhau như: đá gà WS168, đá gà Techplay, đá gà GA28, đá gà ISC.

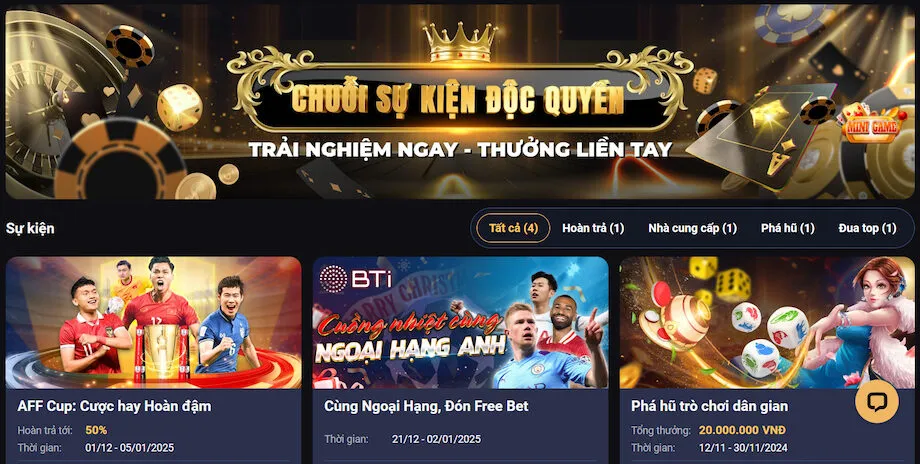

Typhu88 có những khuyến mãi gì?

Cổng game đổi thưởng Typhu88 đang cung cấp nhiều chương trình khuyến mãi hấp dẫn nhằm tạo thêm niềm vui và gia tăng cơ hội chiến thắng cho người chơi. Mỗi sự kiện đều có những đặc điểm riêng biệt và điều kiện tham gia khác nhau. Sau đây là một số khuyến mãi khi anh em tham gia chơi cá cược tại Typhu88:

Hoàn trả không giới hạn 1,25%

Một trong những chương trình khuyến mãi Typhu88 được nhiều người chơi mong chờ nhất đó chính là khuyến mãi hoàn trả. Khi tham gia trải nghiệm cá cược, anh em có thể được cổng game hoàn trả không giới hạn nên tới 1,25% tổng tiền cược hàng ngày. Điểm đặc biệt của chương trình ưu đãi này chính là không giới hạn số vòng cược.

Thưởng nạp ban đầu 110%.

Người chơi mới lần đầu nạp tiền tham gia chơi game Typhu88 có cơ hội nhận gấp đôi tiền nạp với 110% lên đến 18 triệu đồng. Điều kiện tham gia khuyến mãi này là người chơi cần hoàn thành 20 vòng cược trước khi được rút tiền.

Một số câu hỏi thường gặp về nhà cái Typhu88

Bộ phận chăm sóc khách hàng của nhà cái Typhu88 liên tục nhận được những câu hỏi của người chơi mới. Để hiểu rõ hơn về hoạt động cá cược tại sân chơi, anh em bet thủ có thể tìm hiểu một số câu hỏi thường gặp cùng với các câu trả lời chi tiết đã được chúng tôi tổng hợp ngay sau đây.

Chơi cá cược tại Typhu88 có phải là hợp pháp không?

Như đã đề cập ở trên, nhà cái Typhu88 được cấp phép bởi các tổ chức uy tín Malta Gaming Authority (MGA) và Ủy ban cờ bạc Vương quốc Anh (UKGC). Hơn nữa, sân chơi cũng đã khẳng định chất lượng của mình với nhiều ưu điểm nổi bật. Bên cạnh việc duy trì dịch vụ chất lượng dẫn đầu, nền tảng còn được yêu thích bởi hệ thống thanh toán tiện ích và kho game đồ sộ cùng tỷ lệ trả thưởng hấp dẫn.

Đăng ký nhiều tài khoản Typhu88 có được không?

Mỗi người chơi chỉ được tạo 1 tài khoản Typhu88 duy nhất. Sân chơi này đã thiết lập rất nhiều phương thức xác minh danh tính người dùng. Nếu phát hiện game thủ nào sử dụng nhiều tài khoản nhằm trục lợi khuyến mãi hoặc có hành vi bất chính sẽ bị nhà cái Typhu88 xóa tài khoản vĩnh viễn.

Tại sao đã có đăng ký Typhu88 thành công nhưng lại không đăng nhập được?

Nếu người chơi đăng ký tài khoản Typhu88 thành công nhưng không đăng nhập được có thể là do người chơi đã điền sai thông tin đăng nhập. Ngoài ra, anh em cũng có thể kiểm tra xem mình có truy cập vào link Typhu88 có bị chặn hay không. Trong trường hợp link nhà cái xảy ra sự cố, bạn có thể liên hệ với nhân viên chăm sóc khách hàng để được hỗ trợ.

Typhu88 lừa đảo người chơi có phải sự thật?

Thắc mắc nhà cái Typhu88 lừa đảo người chơi có thật hay không đã trở thành tâm điểm chú ý từ cộng đồng cá cược trong những ngày qua.Bởi chất lượng và quy mô lớn hàng đầu của nhà cái này là điều khiến người chơi cảm thấy ngờ vực nhất.

Typhu88 đã khẳng định một cách mạnh mẽ rằng những lời đồn đại về cổng game lừa đảo là hoàn toàn sai sự thật và không có căn cứ. Vì hầu hết những đánh giá tiêu cực về nhà cái này có uy tín không chỉ là quan điểm từ một phía và không có bằng chứng xác thực.

Quy định về tuổi tham gia cá cược trực tuyến trên Typhu88?

Typhu88 yêu cầu người tham gia tuân thủ quy định về độ tuổi khi tham gia hoạt động cá cược trực tuyến. Chỉ những người chơi từ 18 tuổi trở lên mới được phép đăng ký và tạo tài khoản để tham gia trải nghiệm.

Bài viết trên là một số thông tin cần biết về nhà cái Typhu88 – sân cược uy tín, chất lượng hàng đầu trên thị trường cá cược hiện nay. Những ưu đãi hấp dẫn của nhà cái vẫn đang chờ anh em khám phá. Hãy nhanh chóng đăng ký tài khoản cá cược Typhu88 ngay hôm nay để thoải mái chơi game cá cược ăn tiền mọi lúc mọi nơi.